Sultan of Satire

Politics has perhaps never been so ripe for satire as it is now – which is a gift to the likes of cartoonist Gerald Scarfe.

Jonathan Whiley went to meet him at his studio in Chelsea.

The tectonic plates of power have shifted so seismically this summer that making sense of the earthquake has become a unique proposition.

While shock waves continue to reveberate throughout the nation, satirists lampoon the epicentre with wicked relish.

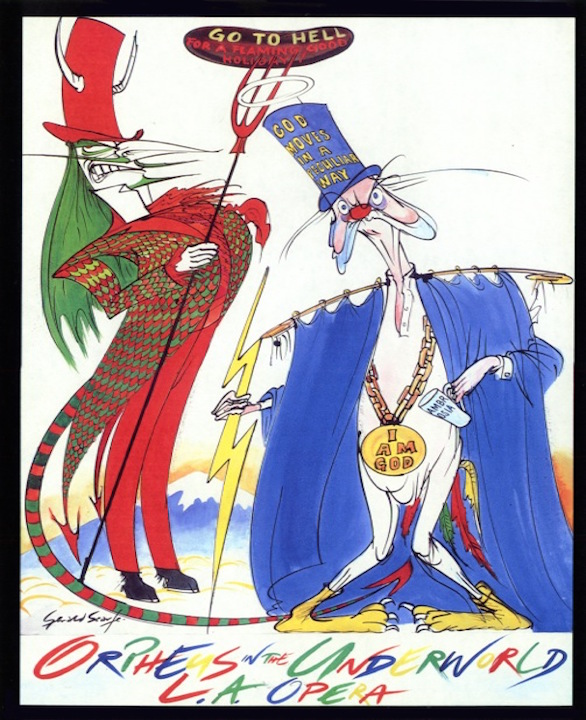

Gerald Scarfe, arguably Britain’s best cartoonist, has been chronicling the political landscape for more than half a century from his sun-drenched Chelsea studio. Spending time within its riotously colourful walls is truly a feast for the eyes. Everywhere you look political heavyweights – quite literally, in the case of Donald Trump – are staring back at you, having been skewered by his satirical eye.

“They’ve been very kind to cartoonists recently,” Gerald says as I glance at the acerbic caricatures that are plastered around the top-floor room. “Cameron and Clegg were a bit bland, but now we’ve got Trump. He’s an absolute monster.”

Having recently returned from a two-week holiday in Bilbao with wife Jane Asher – the actress who until last year also ran a successful cake-making business in Cale Street – Gerald is engaging, candid and relaxed company.

“As Geoffrey Archer said to me (he collects cartoons), it’s all a game, really,” the 80-year-old says. “Although I attack them, they would rather be depicted in a newspaper as a warthog than not. It’s all attention.

“The sad truth is that you can’t get them, as you’re just adding to their fame.”

Nicknamed “the scourge of Westminster”, Gerald’s lampooning of the rich and famous – with cartoons first appearing in Punch and Private Eye during the early Sixties – has attracted its fair share of controversy.

His drawing of Harold Macmillan perched naked on a chair as a parody of the iconic photograph of Christine Keeler during the Profumo scandal raised his profile considerably, and later saw WH Smith ban the sale of the Private Eye Annual.

Previously he’s had to contend with the wrath of feminist Labour MPs, who took exception to a sketch of Angela Merkel breastfeeding Spain and Italy, and he’s had his fair share of uncomfortable personal encounters, including a dinner with Princess Margaret, whom he had depicted as a pig in Private Eye the previous week.

“It was a bit uncomfortable, I suppose,” he says with a wry smile.

Regrets? He’s had a few. He shows me a drawing of legendary war photographer Don McCullin that suggests Don was glorifying war for a glossy magazine, when in fact he came to realise that he was simply trying to tell the truth. “I regret that because Don is a fantastic photographer,” he says. “I’m almost ashamed to mention it to you.”

On another occasion a drawing of Peter Cook, a friend of his, with Dudley Moore as a glove puppet became one that he felt was unfair, and he once let a memory of Edward Heath, who was snotty to him at a meal, play on his mind when drawing him thereafter. “It was wrong, really, because it’s not what he did to me personally, but what he did to the nation that was important,” he says.

His work has not always been a laughing matter, though. He was once sent on a harrowing assignment during the Vietnam War, and was also hijacked, with wife Jane, at gunpoint when he was working in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. “This really dangerous type got in the driver’s seat alongside me, and two guys got in the back next to my wife and they said, ‘This is official,’ and I think what they meant is that they were official IRA,” he recalls.

“They pulled a gun out and stuck it through the gap between the seats into my back.” Eventually Gerald and Jane were told to get out of the car, but not before the younger member of the gang, catching sight of Gerald’s drawing, remarked that he was “a brave drawer”.

“The next day they blew up the post office with my Cortina,” Gerald adds. This is not the only time he has been held up at gunpoint; he was also caught up in a robbery at a hotel in Paris during the making of a BBC film about legendary Vogue photographer Horst P. Horst.

“I went to Paris to talk to Yves Saint Laurent and Karl Lagerfeld, because they were in the Vogue fashion business,” he says. “We were in this tiny hotel and I came downstairs to the front desk and these two men came in with motorcycle helmets on.”One leapt over the counter and got hold of the manager and slammed him up against the wall and he kept saying, ‘Open the safe,’ and the other guy got hold of me and pushed me against the reception guest counter and told me to be quiet.”It was probably four minutes, but it seemed like forever. They ran out of the door and that was it.”

We talk about Chelsea and how much it’s changed over the years; Gerald has had his fair share of neighbours over the last half-century. “Originally it was the Americans who were very rich,” he says. “Now it’s people from Russia or China. There’s a new rich all the time moving through.”

When he was younger, Gerald admits, he spent time at the Chelsea Arts Club to relax, often playing snooker till 3am with the actor David Hemmings.

These days he’ll rise in the early hours to start drawing – often at 5am – and while the couple often dine out at The Five Fields and Colbert, they also enjoy cooking at home, with produce from The Chelsea Fishmonger a staple on their shopping list. Gerald, whose sketches are in the Blue Boar bar of the Conrad St James hotel in Victoria and has a bar named after him at the Rosewood London hotel, didn’t attend art school when he began work.

But it did reach a stage in his career, he says, where he felt a lack of academic acclaim.

“The biggest art school at the time was the Royal College of Art, and I wondered whether I was good enough to get in,” he says. “I felt insecure in my work, as cartoons are never regarded in the same ilk as fine art.

“I applied and they accepted me, and I went and then I left after two weeks. I realised afterwards all I wanted was the acclaim and the knowledge that I was good enough to get in.”

I joke that he’s not done too badly since, and he smiles modestly. “I guess so. You’re never completely satisfied with your career, are you? It’s like you’ve never quite got enough money.”

As he says that I catch sight of a cartoon behind him; a sneering depiction of Tony Blair being showered by gold coins. It’s a timely reminder that Gerald’s satirical eye is, quite literally, bang on the money, and what’s more, his contribution is worth more than its weight in gold.

geraldscarfe.com